Indian Legal System > Civil Laws > Environmental Laws > Sustainable Development > Precautionary Principle

Principle 15 of the Rio Declaration, 1992 declares “Where there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation.”

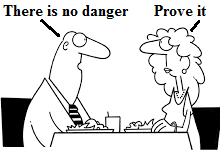

The Precautionary Principle is one of the important principles under the concept of sustainable development. The Principle status as follows – “In order to protect the environment, the Precautionary approach shall be widely applied by states according to their capabilities. Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation”. Thus the precautionary principle states that if there is a risk of severe damage to humans and/or the environment, absence of incontrovertible, conclusive, or definite scientific proof is not a reason for inaction. It is a better-safe-than-sorry approach. It is a proactive approach.

Before the Stockholm Conference, 1972 the approach towards environmental problems was of ‘assimilative capacity’. As per this concept, the natural environment has the capacity to absorb the ill effects of pollution, but beyond a certain limit, the pollution may cause damage to the environment requiring efforts to repair it. Therefore, the role of environmental protection agencies will begin only when the upper limit of the pollution is crossed.

The precautionary approach indicates that lack of scientific certainty is no reason to postpone action to avoid potentially serious or irreversible harm to the environment. At the core of the precautionary principle is the element of anticipation, reflecting a requirement of effective environmental measures based upon actions which take a long-term approach and which might anticipate changes on the basis of scientific knowledge. This approach was adapted in Rio Conference, 1982.

When the impacts of a particular activity such as emission of hazardous substances are not completely clear, the general presumption is to let the activities go ahead until the uncertainty is resolved completely. This approach is reactive approach. The Precautionary Principle counters such general presumptions. When there is uncertainty regarding the impacts of an activity, the Precautionary Principle advocates action to anticipate and avert environmental harm. Thus, the Precautionary Principle favours monitoring, preventing and/or mitigating uncertain potential threats. It is proactive approach.

The precautionary principle

concentrates on prevention rather than cure. The principle embodies the idea of

careful planning to avoid risks in the first place, rather than trying to

determine how much risk is acceptable. Decision-making processes should always

endorse a precautionary

approach to risk management and in particular should include the adoption of

appropriate precautionary measures. Precautionary measures should be based on

up-to-date and independent scientific judgment and be transparent. They should

not result in economic protectionism. Transparent structures should be

established which involve all interested parties, including non-state actors,

in the consultation process. Appropriate review by a judicial or administrative

body should be available

Case Laws

In India, there are lots of environmental regulations, like the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974 and the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981. They are aimed at cleaning up pollution and controlling the amount of pollutants released into the environment.

They regulate the harmful substances as they are emitted rather than limiting their use or production in the first place. These laws are based on the assumption that humans and ecosystems can absorb a certain amount of contamination without being harmed. Thus they have assimilative capacity approach. But the past experience shows that it is very difficult to know what levels of contamination, if any, are safe and therefore, it is better to err on the side of caution while dealing with the environment.

In Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union of India, AIR 1996 SC 2715 case, the Supreme Court accepted that the Precautionary Principle is part of the environmental law of the country and shifted the burden of proof onto the developer or industrialist who is proposing to alter the status. They found it “necessary to explain the meaning of the principles in more detail so that courts and tribunals or environmental authorities can properly apply the said principles in the matters which come before them

In Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union of India, AIR 1996 SC 2715 case, the petitioners filed a petition in the public interest under Article 32 of the Constitution of India, directed against the pollution caused by enormous discharge of untreated effluent by the tanneries and other industries in the State of Tamil Nadu. The tanneries and other industries of Tamil Nadu were discharging their untreated effluent into agricultural fields, road sides, waterways and open lands, and into the river Palar which is the source of water supply to the residents of the area. The water in river and the ground water had been polluted to the high extent that there was non availability of potable water to the residents of the area. 35,000 hectares of agricultural land became partially or totally unfit for cultivation. The court ordered the central Government to constitute an authority and confer on it all powers necessary to deal with the situation. The authority was to implement the precautionary principle and the “polluter pays” principle. It would also identify the families who had suffered from the pollution and access compensation and the amount to be paid by the polluters to reverse the ecological damage. The court required the Madras High Court to monitor the implementation of its orders through a special bench to be constituted and called a “Green Bench” The Court also opined that “though the leather industry is of vital importance to the country as it generates foreign exchange and provides employment avenues it has no right to destroy the ecology, degrade the environment and pose as a health hazard”. The Court recognized that a balance must be struck between the economy and the environment.

In M. C. Mehta v. Union of India, AIR 1997 SC 734 case, popularly known as the Taj Trapezium case which refers to an area of 10,400 sq. km. trapezium shaped area around Taj Mahal covering five districts in the region of Agra. Taj Mahal is one of the most popular and beautiful monuments in the world. Taj is one of the best examples of Mughal architecture in India. It was declared as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983. In 1984, M.C. Mehta, a public interest lawyer, and environmentalist visited Taj Mahal. He saw that the monument’s marble had turned yellow and was pitted as a result of pollutants from nearby industries. This compelled Mehta to file the petition before the Supreme Court. The Court applied the ·’Precautionary Principle’ as explained by it in Vellore Case and opined that “The environmental measures must anticipate, prevent and attack the causes of environmental degradation. The ‘onus of proof’ is on the industry to show that its operation with the aid of coke/coal is environmentally benign. It is rather, proved beyond doubt that the emissions generated by the use of coke/coal by the industries in TTZ are the main polluters of the ambient air”.

The Court ordered the industries to change-over to the natural gas as an industrial fuel or stop functioning with the aid of coke/coal in the Taj trapezium and relocate themselves as per the directions of the Court.

In this case the Supreme Court has explained the ‘Precautionary Principle’ in the context of the municipal law as under-

- Environmental measures by the State Government and the statutory authorities must anticipate, prevent and attack the causes of environmental degradation.

- Where there are threats of serious and irreversible damage, lack of scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation.

- The ‘onus of proof’ is on the actor or the developer/industrialization to show

that his action is environmentally benign”.

In M. C. Mehta v. Union of India, (1997)2 SCC 411,430 case commonly known as Calcutta Tanneries Case, the Court ordered the polluting tanneries operating in the city of Calcutta (about 550 in number) to relocate themselves from their present location and shift to the new leather complex set up by the West Bengal Government.

In M.C. Mehta v. Union of India, (1997)3 SCC 715,720 case, commonly known as Badkhal & Surajkund Lakes Case, the court relied on the ‘Precautionary Principle’. The Court held that the ‘Precautionary Principle’ made it mandatory for the State Government to anticipate, prevent and attack the causes of environmental degradation; The Court had no hesitation in holding that in order to protect the two lakes from environmental degradation it was necessary to limit the construction activity in the close vicinity of the lakes.

The Supreme Court felt the need to explain the meaning of the Precautionary Principle in more detail and lucid manner so that Courts and tribunals or environmental authorities can properly apply the said principle in the matters which might come before them. In A.P. Pollution Control Board v. Prof M. V Nayudu, AIR 1999 SC 812 case, tracing the evolution of precautionary principle the Court observed that “Earlier, the concept was based on the ‘assimilative capacity’ rule as revealed from Principle 6 of the Stockholm Declaration of the U.N. Conference on Human Environment, 1972. The said principle assumed that science could provide policymakers with the information and means necessary to avoid encroaching upon the capacity of the environment to assimilate impacts and it presumed that relevant technical expertise would be available when environmental harm was predicted and there would be sufficient time to act in order to avoid such harm. But in the 11th Principle of the U.N. General Assembly Resolution on World Charter for Nature, 1982, the emphasis shifted to the ‘Precautionary Principle’, and this was reiterated in the Rio Conference of 1992 in its Principle 15.”

The Court opined that the inadequacies of science were the real basis that had led to the Precautionary Principle of 1982. It was based on the theory that it is better to err on the side of caution and percent environmental harm which may indeed become irreversible. The principle of precaution involved the anticipation of environmental harm and taking measures to avoid it or to choose the least environmentally harmful activity.

The Court adopted the view that “Environmental Protection should not only aim at protecting health, property and economic interest but also protect the environment for its own sake. Precautionary duties must not only be triggered by the suspicion of concrete danger but also by justified concern or risk potential”.

In this case M. Jagannadha Rao, J. noticed, while the inadequacies of science had led to the ‘Precautionary Principle’, the said principle in its turn led to the special principle of burden of proof in environmental cases. In environmental cases, the absence of injurious effect of the actions proposed was placed on those who wanted to change the status quo. This is often termed as a reversal of the burden of proof. Thus the burden of proof lies on the party who wants to alter the status quo. Thus, the court by explaining the concept of the precautionary principle and the new concept of the onus of proof in environmental cases paved the way for greater

application of this principle in the future.

In Narmada Bachao Andolan v. Union of India, AIR 2000 SC 3751 case, the Supreme Court decided the issues relating to construction of a dam on Narmada River which was a part of the Sardar Sarovar Project. Explaining the new concept of burden of proof the Court held that the ‘Precautionary Principle’ and the corresponding burden of proof on the person who wants to change the status quo will ordinarily apply in a case of polluting or other project or industry where the extent of damage likely to be inflicted is unknown. Where the effect on the ecology of the environment of setting up of industry is known, the Court held that “What has to be seen is that if the environment is likely to suffer, then what mitigative steps can be taken to offset the same. Merely because these will be a change is no reason to presume that there will be an ecological disaster. It is when the effect of the project is known then the principle of sustainable development would

come into play which will ensure that mitigative steps are and can be taken to preserve the ecological balance”.

The Court concluded, what was the impact on the environment with the construction of a dam was well known in India, the dam was neither a nuclear establishment nor a polluting industry, and therefore, the decision in A.P. Pollution Control Board’s Case would have no application in this case.

Conclusion

It is clear that the law on sustainable development is gaining momentum at the local, national, regional, and international levels. The role of the judiciary in relation to the law of sustainable development is thus of the greatest importance. As an offshoot of judicial recognition, the National Environmental Policy adopted the precautionary principle as a guiding principle. However, it is still a long way to go before the precautionary principle takes its rightful place in Indian environmental laws and even more importantly gets effectively implemented.

Previous Topic: Intergenerational Equity Principle

Next Topic: Polluter Pays Principle