Indian Legal System > Civil Laws > Environmental Laws > Sustainable Development > Principle of Equity and Equality

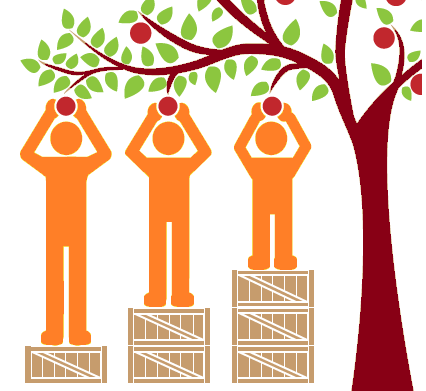

Economic growth can only be sustained when it is based on the principle of equity and equality. Common ownership of resources and their equitable distribution is a fundamental tenet of the idea of the modern welfare state. Equity means that there should be a minimum level of income and environmental quality below which nobody falls. Within a community, it usually also means that everyone should have equal access to community resources and opportunities and that no individuals or groups of people should be asked to carry a greater environmental burden than the rest of the community as a result of government actions.

The terms ‘equity’, ‘fairness’ and ‘justice’ are often used interchangeably, although they involve subtle differences. We can understand the concept of equity from following factors:

- Equality of opportunity to achieve one’s potential

- An equal share of benefits for relevant stakeholders in specific contexts (equity of outcomes)

- At the macro-level, reduced disparities in income and wealth (Economic equality).

- A ‘fair’ distribution of benefits and costs of a particular public policy, or a fair allocation of public funds, resources, spaces, including natural resources.

- Positive discrimination and redistribution to right historic wrongs or in favour of systematically disadvantaged groups, including disadvantages of economic, social, gender and other positions in society (Social equality).

- Empowerment to enable access to information, fair representation, meaningful participation in decision-making, bargaining and effective remedy (Equity of process).

- Equity between nations, or international equity that operates in the realm of inter-societal relations

- Global equity on the basis of identities that transcend national boundaries, such as gender, membership of an indigenous community or the particularly vulnerable in some form.

For Sustainable Development, all above aspects should be addressed. A one-sided emphasis on any single one of these aspects considerably distorts the meaning of equity.

Social justice and equity explicitly demand additional attention to historical inequities and discrimination, and also to the initial allocation of resource rights and opportunities. Thus, bringing together sustainability and equity also infers the need for transformation of social relations, redistribution of rights and resources, and policy approaches which address social, economic and environmental concerns simultaneously and holistically

Objectives of the Principle:

- To meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

- To provide fair treatment or respecting the rights of non-human living organisms, those who are sentient but do not have a voice. It should be noted that fairness to non-humans follows fairness within humanity.

- To persuade individual, even while pursuing a legitimate livelihood, not to negatively affect the health and rights of another person.

- To guarantee equitable access to natural resources and environmental sinks. The equitable distribution of the socio-economic benefits from the use of natural resources depends critically on how initial rights to resource use are granted. Equally efficient distributions of rights to resources may lead to very different outcomes in terms of equity.

- To safeguard the vulnerable section during development. If the poor are directly dependent on natural resources such as forests for firewood, pastures for grazing or scarce water resources for survival, then the environmental degradation aggravates poverty, and thereby accentuates inequity in society.

- To guarantee a fair allocation of resource rights so that it would result in individuals and communities cooperating in the collective management of the resource.

Article 39 of the Constitution

The Constitution of India vide in its Article 39 also provided the policy of sustainable development to be adopted by the state. The state is the legal owner and trustee of its people and it must ensure that the process of distribution is guided by the doctrine of equality and the larger public good. Sustainable development can happen only when it happens for all. Right to livelihood has been declared by the constitutional courts of India as a part and parcel of the fundamental right to life guaranteed under Article 21 of the constitution of India. To ensure the fundamental right to livelihood is fundamental to the state policy and it must be ensured through equitable distribution of resources.

Provisions of Article 39 of the Constitution Of India:

Certain principles of policy to be followed by the State: The State shall, in particular, direct its policy towards securing

(a) that the citizens, men and women equally, have the right to an adequate means to livelihood;

(b) that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community are so distributed as best to subserve the common good;

(c) that the operation of the economic system does not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment;

(d) that there is equal pay for equal work for both men and women;

(e) that the health and strength of workers, men and women, and the tender age of children are not abused and that citizens are not forced by economic necessity to enter avocations unsuited to their age or strength;

(f) that children are given opportunities and facilities to develop in a healthy manner and in conditions of freedom and dignity and that childhood and youth are protected against exploitation and against moral and material abandonment

Case Laws:

In Hinch Lal Tiwari v Kamala Devi and Others, AIR 2001 SC 3215 case, the court held that “It is important to notice that the material resources of the community like forests, tanks, ponds, hillock, mountain, etc. are nature’s bounty. They maintain a delicate ecological balance. They need to be protected for a proper and healthy environment which enables people to enjoy a quality life which is the essence of the guaranteed right under Article 21 of the Constitution”.

In Centre for Public Interest Litigation and Others. v. Union of India and Others, (2012) 3 SCC 1 case, the Court defined resources of the country. It said, “At the outset, we consider it proper to observe that even though there is no universally accepted definition of natural resources, they are generally understood as elements having intrinsic utility to mankind. They may be renewable or nonrenewable. They are thought of as the individual elements of the natural environment that provide economic and social services to human society and are considered valuable in their relatively unmodified, natural, form. A natural resource’s value rests in the amount of the material available and the demand for it. The latter is determined by its usefulness to production. Natural resources belong to the people but the State legally owns them on behalf of its people and from that point of view natural resources are considered as national assets, more so because the State benefits immensely from their value. The State is empowered to distribute natural resources. However, as they constitute public property/national asset, while distributing natural resources, the State is bound to act in consonance with the principles of equality and public trust and ensure that no action is taken which may be detrimental to public interest. Like any other State action, constitutionalism must be reflected at every stage of the distribution of natural resources. In Article 39(b) of the Constitution it has been provided that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community should be so distributed so as to best sub-serve the common good, but no comprehensive legislation has been enacted to generally define natural resources and a framework for their protection. of course, environment laws enacted by Parliament and State legislatures deal with specific natural resources, i.e., Forest, Air, Water, Costal Zones, etc. The ownership regime relating to natural resources can also be ascertained from international conventions and customary international law, common law and national constitutions. In international law, it rests upon the concept of sovereignty and seeks to respect the principle of permanent sovereignty (of peoples and nations) over (their) natural resources as asserted in the 17th Session of the United Nations General Assembly and then affirmed as a customary international norm by the International Court of Justice in the case opposing the Democratic Republic of Congo to Uganda. Common Law recognizes States as having the authority to protect natural resources insofar as the resources are within the interests of the general public. The State is deemed to have a proprietary interest in natural resources and must act as guardian and trustee in relation to the same. Constitutions across the world focus on establishing natural resources as owned by, and for the benefit of, the country. In most instances where constitutions specifically address ownership of natural resources, the Sovereign State, or, as it is more commonly expressed, the people’, is designated as the owner of the natural resource.”

Court further said “As natural resources are public goods, the doctrine of equality, which emerges from the concepts of justice and fairness, must guide the State in determining the actual mechanism for distribution of natural resources. In this regard, the doctrine of equality has two aspects: first, it regulates the rights and obligations of the State vis-vis its people and demands that the people be granted equitable access to natural resources and/or its products and that they are adequately compensated for the transfer of the resource to the private domain; and second, it regulates the rights and obligations of the State vis-vis private parties seeking to acquire/use the resource and demands that the procedure adopted for distribution is just, non-arbitrary and transparent and that it does not discriminate between similarly placed private parties.”

In Nagesh v. Union of India, 1993 JLJ746 case, the Court ruled that “in its initial stage the directive principles were approached, considered and treated in a pure legalistic approach but there have been cases pointing to bold steps towards a social welfare concept of the State in an era of judicial activism giving new dimension to these directive principles. Article 39(b) of the Constitution provides for equitable distribution of material resources. And this word ‘distribution’ used in Article 39(b) need to be liberally construed so as to give full and comprehensive effect to the mandate of equitable distribution as contained in Article 39(b) of the Constitution”.

Conclusion:

Equity is supposed to be a central ethical principle of sustainable development. An emphasis on equity highlights the importance of good governance, redistribution of income and wealth, empowerment, participation, transparency, and accountability. Thus, while different groups will often have different ideas about what constitutes ‘fairness’ or ‘justice’, equity enables diverse groups to have their voices heard in these debates in specific contexts.

Previous Topic: Public Trust Doctrine

One reply on “Principle of Equity and Equality”

Really Good Image